Dr Francesca Piana

Post-doctoral Fellow of the Swiss National Science Foundation, honorary research fellow at the Department of History, Classics and Archaeology of Birkbeck College

Papiers d'actualité / Current Affairs in Perspective

Fondation Pierre du Bois

No 5, June 2015

Read, save or print the pdf version of this article.

Ruth Azniv Parmelee was an American medical missionary.i She was born in 1885 in the city of Trebizond in the Ottoman Empire. Parmelee died in 1973 in a house for American missionaries in Massachusetts, where she had moved after she retired in the early 1950s. She was a woman who worked for other women. Her main specialties were obstetrics and the training of nurses.ii Parmelee mainly lived and worked in the Ottoman Empire, then Turkey and Greece. Her first mission as a young medical doctor was in the American missionary station of Harpoot, now Kharpert, Turkey. A few months after her work in the mission commenced, the Armenian genocide began. Parmelee thus happened to be one of the foreign witnesses of the planned extermination of the Armenian minority in the Ottoman Empire.iii

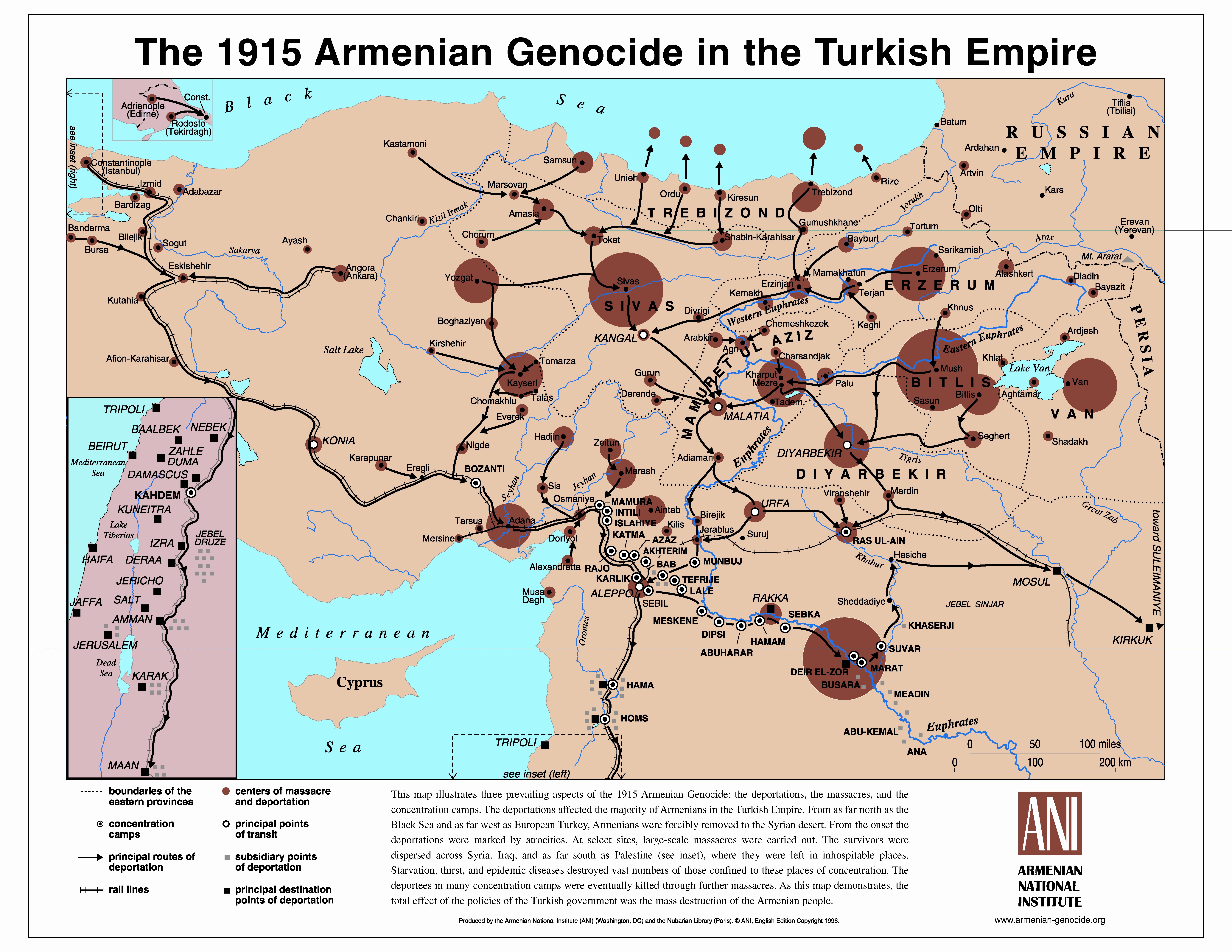

One century has passed since the Armenian genocide tragically marked the history of the 20th century. On 24 April 1915, 250 Armenian intellectuals living in Istanbul were incarcerated and the majority of them were later killed. Over the course of the following months and years, able-bodied Armenian men were massacred or enrolled in forced labor, whereas women and children were deported through the Mesopotamian desert and exposed to hunger and violence. For men, women, and children, the unfortunate outcome was often death. Estimations report that between 800,000 and 1.5 million Armenians perished between 1915 and 1922.iv The following map illustrates the geography of the Armenian genocide. Harpoot, the place where Parmelee lived and worked, is situated along the Euphrates River.

(courtesy of the Armenian National Institute)

Parmelee was born into an American missionary family that worked for the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions. Her father, Moses Payson Parmelee, was also a medical doctor. The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions – a very influential American missionary organization – was created at the beginning of the 19th century and dispatched its missionaries among Native Americans as well as in far away countries with the goal of evangelization. Missionary stations were also created in the Ottoman Empire. While Ottoman rule prohibited the conversion of Muslims, American missionaries began proselytizing non-Muslim groups, including Armenians. Over the decades, as direct proselytism faded other programs, such as education, health, and livelihoods, rose to prominence.vi

Since her childhood and until her death, Parmelee was a keen and prolific writer. She was only 10 years old when she addressed a letter to her mother that provided vivid details about the number of Armenians killed during the Hamidian massacres of 1894-6.vii Later on, as a medical missionary, she wrote letters to her family and congregation back in the United States, describing her work and providing many details about the people she lived with and those she worked for. In the documents she also sketched her own understanding of her missionary and medical work and engaged with the political, economic, and social situations of the countries in which she lived.

Contrary to many of her colleagues in the mission of Harpoot who recorded their personal memories during and after the end of the Armenian genocide, Parmelee refrained from doing so.viii It was only later in her life, in the mid-1960s, that she decided to write about her years among the Armenians in the form of a short book entitled "A Pioneer in the Euphrates Valley."ix Why did Parmelee take 40 years to write her memories of the Armenian genocide? The documents do not tell. Maybe the suffering Parmelee witnessed was too atrocious for her to write about at the time. Maybe she compartmentalized and preferred staying active and busy, instead of taking time for reflection.

It was common for missionary and relief workers to leave written traces of their experiences in the mission. Writing is a form of witnessing, a way to communicate, a means of providing evidence of the work accomplished, and, in a time of crisis, a form of personal preservation. Referring to the representation of humanitarians in refugee history, Peter Gatrell observes that the narratives of relief workers and humanitarians are often constructed as a path towards the consolidation of personal identity, the latter of which emerged when they assisted refugees and people in need.x Gatrell continues by stressing that in these narratives, humanitarians are the holders of the memory and the main agents of the story, whereas recipients of humanitarian aid are often marginalized.xi

The world in which Parmelee wrote her memories of the Armenian genocide was very different from the one she lived in as a young female doctor. The 1960s in the United States was a period when American society was going through the radicalization of the racial question, the emergence of the civil rights movement, the war in Vietnam, and the assassinations of John F. Kennedy and Martin Luther King. Moreover, Parmelee wrote her memories away from the places where the genocide had occurred and away from most of the people with whom she lived during the time of the genocide. Parmelee's writing produced a book where questions of memory, trauma, identity, professional achievements, gender, and inter-personal relations intertwined with broader themes. These are the Armenian genocide, the fragile peace settlements that resulted from the victory of Kemalist Turkey and the Lausanne Treaty, as well as the role of missionaries at the beginning of the 20th century.

A large part her book deals with the deportation and massacres of the Armenians. Parmelee recalls the militarization of Turkey in the weeks following the murder of Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo. She reports what happened to the Armenians of Harpoot. Prominent Armenian men were killed before the actual deportations started. Many of those killed and deported on an "unknown journey" – historical work since then has revealed what actually happened to the deportees – were connected to the work of the American mission or were friends of Parmelee and the American staff. In writing about the surviving Armenians she worked with, Parmelee says: "the sight of these pitiful exiles haunted me for days; they acted like beasts and not like human beings. All they could think about was bread, bread for which they clamored."xii

Parmelee's book is about the Armenian genocide as well as the (re)negotiation of her gender role and professional identity in a period of crisis and in a pivotal moment in the development of her life and career. As far as her private life is concerned, Parmelee never married. By the end of the first two decades of the 20th century, skilled women who were single were no longer new to foreign missions. For instance, the American Women's Board of Missions was established in the 1870s and, from its outset, sent single women abroad. However, there were more female educators and nurses in the missions than female doctors. In that respect, Parmelee was right in defining herself as a pioneer – "the first woman doctor to practice medicine in the Harpoot region."xiii The American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions hired Parmelee as a female doctor to work in particular among Armenian women. Later on, due to the highly gendered dimension of the Armenian genocide, where the men were killed and the surviving women and children were in desperate conditions, Parmelee's work became of crucial importance. Within the framework of the collective rehabilitation of the Armenian community, Parmelee was put in charge of the medical examination of Armenian women who had "had contact" – a euphemism for rape – with Turkish or Kurdish men.xiv

Unlike her father, and contrary to her male doctor colleagues in the mission of Harpoot, Parmelee could not rely on the proximity and support of a husband. She travelled to Harpoot with her aging mother, for whom, as a daughter, she was responsible to take care of. But being single and abroad also came with advantages. Parmelee challenged gender limits of the American society where female professionals were the minority compared to men, and the number of female doctors was even smaller. She describes herself as "bold enough" to ride her horse wearing a "divided cotton skirt" instead of sidesaddle, which was still the most common riding practice for women at that time. She seems to have enjoyed a sense of freedom and professional development that she might not have experienced had she stayed in the United States as a doctor.xv Within the mission, Parmelee also negotiated a personal – yet racialized – space, which was different from the institution of marriage and the institution of the mission itself. This materializes through the relationships of trust, affection, and support that she established especially with Armenian nurses and other female foreign relief workers, whom she turned to in her daily life.xvi

In 1922, at the age of 37, Parmelee left the mission of Harpoot – she was deported with the other American and foreign missionaries from Turkey during the last phase of the Greco-Turkish war. After spending the summer in the United States, she was supposed to return to the city of Smyrna, the present Izmir, in Asia Minor. In the meantime, the Greek army was defeated, the Turkish army entered Smyrna, and in the course of one month hundreds of thousands of Ottoman Greeks and Armenians were evacuated from Smyrna to Greece in what would become one of the more dramatic "population transfers" of the 20th century. In October 1922, Parmelee went to work as a medical doctor for another American organization, the American Women's Hospitals, in Salonika, where many of the refugees ended up. "I now began, this time in Greece, a period of service which lasted thirty years" – Parmelee writes as the last sentence of her book.

By studying both the private and professional life of Ruth Parmelee, I aim to examine some of the most significant historical processes and events of the 20th century. Through the prism of Parmelee, I am shedding new light to the Armenian genocide, the increasing role of women in the medical profession, the connection of gender and the mission, as well as processes of secularization of humanitarian aid in the first half of the 20th century. Acting from "the margins" of what was a highly male world, Parmelee was a catalyst of social and political change.xvii

Bibliogrpahy

i) I am conducing research on Ruth A. Parmelee within the framework of my current project, entitled "'Parallel Lives': Women, Imperialism, and Humanitarianism, ca. 1880-1950." Thanks to Felix Ohnmacht for his comments on this paper.

ii) See the work of Ellen Fleischmann, "'I Only Wish I Had a Home on This Globe': Transnational Biography and Dr. Mary Eddy," Journal of Women's History 21, no. 3 (2009): 108–30. Virginia Metaxas, "Ruth A. Parmelee, Esther Lovejoy, and the Discourse of Motherhood in Asia Minor and Greece in the early Twentieth Century," in Ellen Singer More, Elizabeth Fee, and Manon Parry, eds., Women Physicians and the Cultures of Medicine (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2009).

iii) Archives of the Houghton Library, ABCFM, ABC 77.1, box 56, Outline of the work of Dr. Ruth Parmelee.

iv) The literature on the Armenian genocide is vast. See the path-breaking work of Taner Akçam, A Shameful Act: The Armenian Genocide and the Question of Turkish Responsibility, Armenian Genocide and the Question of Turkish Responsibility (New York, NY: Metropolitan Books/Holt, 2006) and equally path-breaking work by Ronald Grigor Suny, Fatma Müge Göçek, and Norman M. Naimark, A Question of Genocide: Armenians and Turks at the End of the Ottoman Empire (Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), where contributions present a nuanced narrative of the various historical processes at the origin of the Armenian genocide.

v) Produced by the Armenian National Institute @ANI (Washington DC) and Nubarian Library (Paris). (last seen 8 June 2015, http://www.teachgenocide.org/files/DocsMaps/Map%20of%20the%20Armenian%20Genocide.pdf)

vi) Julius Richter, A History of Protestant Missions in the Near East (New York: F.H. Revell, 1910). Ussama Samir Makdisi, Artillery of Heaven: American Missionaries and the Failed Conversion of the Middle East (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 2008). Heleen Murre van der Berg, New Faith in Ancient Lands. Western Missions in the Middle East in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries (Leiden, Boston, Brill: 2006).

vii) Hoover archives, Private Papers of Ruth Parmelee, box 1, Letter by Ruth Parmelee to Mother and Julius.

viii) See for instance Mabel Evelyn Elliott, Beginning Again at Ararat (New York, Chicago [etc.]: Fleming H. Revell company, 1924). Maria Jacobsen, Diaries of a Danish Missionary: Harpoot, 1907-1919, ed. Ara Sarafian, trans. Kristen Vind (Princeton; Reading, England: Taderon Pr, 2001). Stanley Elphinstone Kerr, The Lions of Marash: Personal Experiences with American Near East Relief, 1919-1922 (SUNY Press, 1973). Esther Pohl Lovejoy, Certain Samaritans (New York: The Macmillan company, 1927). Henry H. Riggs, Days of Tragedy in Armenia: Personal Experiences in Harpoot, 1915-1917 (Ann Arbor, Mich.: Gomidas Institute, 1997).

ix) Ruth A. Parmelee, A Pioneer in the Euphrates Valley (Princeton, N.J., Gomidas Institute: 2002).

x) Peter Gatrell, "Population Displacement in the Baltic Region in the Twentieth Century: From 'Refugee Studies' to Refugee History," Journal of Baltic Studies 38, no. 1 (March 1, 2007): 54.

xi) Gatrell, "Population Displacement in the Baltic Region in the Twentieth Century": 54.

xii) Parmelee, A Pioneer in the Euphrates Valley, 24. Italics in the text.

xiii) Parmelee, A Pioneer in the Euphrates Valley, 1.

xiv) Parmelee, A Pioneer in the Euphrates Valley, 54.

xv) Parmelee, A Pioneer in the Euphrates Valley, 9.

xvi) Carroll Smith-Rosenberg, "The Female World of Love and Ritual: Relations between Women in Nineteenth-Century America," Signs 1, no. 1 (October 1, 1975): 1–29.

xvii) Natalie Zemon Davis, Women on the Margins: Three Seventeenth-Century Lives (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1995).

Mise à jour le Mercredi, 05 Août 2015 04:13