The Great Transformation? Reassessing the Causes and Consequences of the End of the Cold War

24 – 26 September 2015

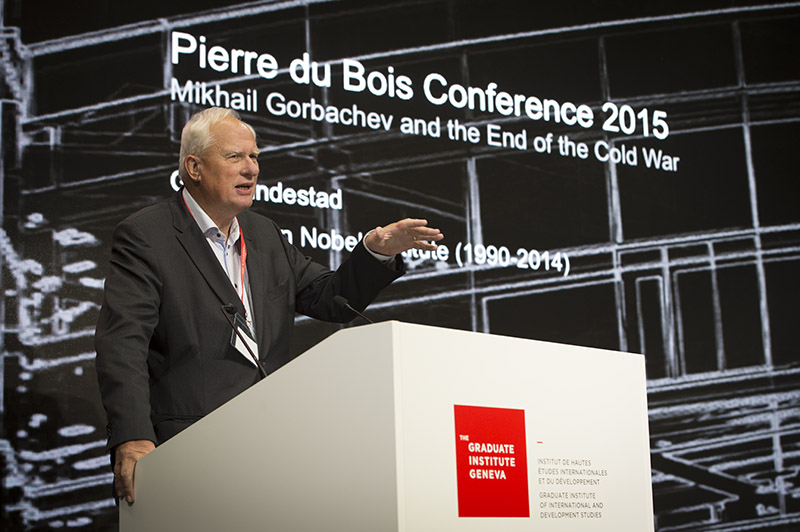

This academic conference aimed to move beyond the simple identification of individual protagonists (the winners or the losers), while focusing on the processes and interactions that climaxed with the developments of 1989-1991 (from the fall of the Berlin Wall to the collapse of the Soviet Union). The conference also featured two special keynote lectures, one by historian Geir Lundestad, former Director of the Nobel Institute, and the other by historian Odd Arne Westad, Harvard University.

At the moment, the state of research on the causes and consequences of the end of the Cold War – necessarily still at its initial phase – seems to have focused on isolated themes (e.g. the role of such individuals as Ronald Reagan or Mikhail Gorbachev; the impact of the human rights movements; the consequences of the economic reforms in the Soviet bloc), largely independent and detached from each other.

Please click here to see the conference programme and here to see the photo gallery. The lecture of Geir Lundestad is available for viewing here and an interview with him is also available here.

This conference is organised by the Institute’s Department of International History, in partnership with the Pierre du Bois Foundation, with support from the Swiss National Science Foundation.

Conference Report

The international conference “The Great Transformation? Reassessing the Causes and Consequences of the End of the Cold War” was held at the Graduate Institute in Geneva on 24-26th September 2015. The purpose of the conference was to move beyond the simple identification of individual protagonists (the winners or the losers), while focusing on the processes and interactions that climaxed with the developments of 1989-1991 (from the fall of the Berlin Wall to the collapse of the Soviet Union). Moreover, by searching for the roots of some of the issues that have dominated the international scene since the 1990s, the conference also discussed the relevance of the events to the post-Cold War era. The conference brought together many of the most prominent senior academics working on the topic, while also providing a platform for emerging young scholars based both in Switzerland and abroad.

During the first two panels of the conference, American and Soviet key personalities were discussed against the background of the controversial question of who actually “won” the Cold War. The first panel discussed Ronald Reagan’s role in the ending the Cold War. It challenged the general simplistic notions surrounding Reagan’s alleged hardline foreign policy. The panel assessed Reagan’s early efforts for quiet diplomacy with the Soviet Union based on the idea of “peace through strength,” as well as the incoherencies of Reagan’s approach as seen by some of America’s key NATO allies. The panelists underlined that although Reagan is considered the president who defeated communism and “won” the Cold War, the administration’s policy decisions were at times confused and often misguided, particularly in regard to the perception of Soviet strength and American decline.

The second panel focused on Soviet personalities, particularly on Mikhail Gorbachev. The Soviet leader’s role in ending the Cold War emerged as crucial. He grasped the inherent problems of the communist regimes in Eastern Europe and, breaking with previous Soviet policies, decided against the use of force to keep the Soviet sphere of influence together. However, it was underlined, Gorbachev’s purpose was not to weaken the Soviet Union but to strengthen it through reforms and liberalization. The Soviet leader’s “vision” – that obviously did not materialize – was to initiate a process of global change in which the Soviet Union would continue to play a key role in a new “common European home.” In this light, many of the current issues in American-Russian relations and in European-Russian relations can be traced to the failure of Gorbachev’s objectives: Russia did not find its place in a renewed European community. Consequently, the anticipation of participation led to realization of exclusion. Therefore, the panelists suggested that the question to be asked is not so much who won the Cold War, but who thought had won. The US perception of victory, in fact, made it assume that it could dictate the terms of the new European settlement, in essence excluding Russia from the post-Cold War order.

The third panel discussed economic developments and interactions leading to the end of the Cold War. The panel focused on Germany (East and West), Poland and Hungary, and the democratic transition in Estonia. The first point made was that economic motivations played a key role in the rapprochement of two Germanies. The second point was that the democratic elections in Poland and Hungary could also be explained on the basis of economic considerations: economic hardship was mitigated by increased political freedom. The third point was that the role of technocrats and pre-Cold War Nordic cooperation was important in Estonia’s smooth transition towards a market-driven economy and integration with the West. The three panelists agreed that while the end of the Cold War came as a surprise to many, in economic terms the Baltic and some Eastern European economic policy-makers had been looking beyond the East-West divide from the early 1980s.

The last panel of the first day was a roundtable discussion on accessing sources on the end of the Cold War. The panelists underlined that the work of historians has always been dependent on the sources made available to them, but some specific developments following the end of the Cold War provided both challenges and opportunities for historians. First, the end of the Cold War led to the willingness of governments to declassify documents. This development was, however, only temporary, as both the US and Russia later slowed down the declassification process or limited the availability of documents. Second, in the US the increasing difficulty of accessing documents is connected to decreasing financial resources allocated to archives. Electronic record systems, keyword searching and absence of finding aids constitute new challenges for historians as they seek both pertinent and novel documentation. Third, the growth of email as a means of communication is providing a further challenge to historians, especially because regulations on archiving and accessing emails of key decision-makers are developing too slowly.

The first day ended with Geir Lundestad’s keynote speech entitled “A prize winning performance: Mikhail Gorbachev, the Nobel Peace Prize and the End of the Cold War.” Lundestad underlined that the importance and global significance of the Nobel Peace Prize is directly related to the discussions and debates that surround the Nobel Committee’s decision every year. The prize awarded to Gorbachev was no exception. The decision was criticized since Gorbachev was the leader of a Marxist-Leninist one-party state, which called into question his peaceful and democratic nature. However, Lundestad argued that Gorbachev’s decisions on a more open government, the initiation of reforms in the Soviet Union and, most importantly, his repudiation of the use of force to crush public protests motivated the Committee’s decision to award the prize. And, considering the crucial role that such policies had in overcoming the Cold War, Lundestad concluded that, from his point of view, the Nobel Peace Prize was well deserved.

The first panel of the second day focused on Western European developments. The panelists emphasized that the end of the Cold War should not be seen only as a result of evolving US-USSR relations, but as a process where European developments also played a crucial role. In particular, the success of the European single market encouraged Gorbachev to image a role for the Soviet Union within the common European home. The evolution of the German question was equally important. The transformation of Germany’s role and power as a consequence of the end of the Cold War, resulting in a unified nation, can lead to asking whether it was actually Germany who “won” the Cold War. Crucially, the crux of German power moved away from military strength to economic power. The role of peace activists in ending the Cold War was also discussed. In the case of the Dutch Inter-Church peace council, the activists remained isolated from decision-makers, making their influence and impact on the transformations that led to the end of the Cold War rather limited.

The second panel of the second day focused on developments in Eastern Europe. The importance of European détente was underlined as a crucial factor in overcoming the Iron Curtain, especially in the case of the Austria-Hungarian relationship. In discussing the special case of Romania, the traditional image of an “independent” foreign policy was challenged by arguing that, in fact, Ceausescu’s policies were only possible within a bipolar world. As the Soviet bloc moved to reform itself in the second part of the 1980s, Romania found itself isolated from both the West and the East. The panel also focused on intelligence agencies in the Eastern bloc and on their failure to provide accurate information to policymakers on the need to reform. This was suggested as another cause in the process that led to the end of the Cold War.

The third panel of the second day assessed American policies in face of the rise of Islamism. It was emphasized that America’s support of the Afghan mujahedeen was motivated by a firm Cold War logic, from the beginning to the end of the 1980s. The role of such policies in ending the Cold War was thus questioned, as America continued to view the world in bipolar terms. Similarly, the dramatic evolution of US-Iranian relations following the Iranian revolution can only be explained on the basis of the Cold War paradigm. Washington’s policymakers in fact misperceived and misunderstood the rise of Islamism in Iran, with consequences that last to the present day.

The second day’s keynote speech was delivered by Odd Arne Westad and was entitled: “Did the Cold War really matter?” Westad argued that the Cold War should not be considered the central theme of the 20th Century. He underlined that not only should the Cold War be decentralized, in the search for its effect in the periphery, but also that it is equally important to situate the Cold War within the broader evolution of the 20th Century. Westad mentioned several key developments that are not directly related to the Cold War, but that nonetheless transformed the international system and the lives of individuals: first, the two world wars, with the destruction of Europe and the consequent rise of the United States as a world power; second, the decolonization process; third, European integration and the rise of China as a world power – developments that can be connected to the Cold War but cannot be explained solely by it.

The second day ended with a roundtable discussion organized in the context of the IHEID and GSCP History and Policy-making Initiative, which focused on potential lessons from the Cold War for current policy-makers. The discussion was wide-ranging, as speakers covered such topics as the interconnection between history and international relations (and the failure of IR scholars to “predict” the end of the Cold War); the legacy of the Cold War on US-Russia relations; the impact of nuclear weapons on international stability, from the Cold War to the present day; the rise of Islamism within the Cold War context and its development since the end of the Cold War; and the importance of multilateral negotiations, drawing from the experience of the CSCE. While there was consensus on the need for more historically-informed policies in current foreign policy-making, the panelists also cautioned on drawing too many parallels with the Cold War, given the complexity of today’s challenges, which are generally of a different nature compared to the ones of the bipolar international system.

The first panel of the third day discussed the emergence of non-state actors on the international scene as a consequence of the end of the Cold War. The panel assessed how private companies increasingly took on responsibilities previously considered the sole prerogative of the state, as in the case of private military companies in Africa. The panel also focused on the multiplication of humanitarian actors – specifically in the context of war-torn Afghanistan – and on how non-governmental organizations coordinated relief aid independently from the governments involved in the conflict. This unveiled how these new international actors potently emerged on the world scene during the last decade of the Cold War, setting the stage for their further development in the post-Cold War era.

The second panel of the third day focused on the interconnection between nuclear arms control negotiations and the end of the Cold War. The role of European public opinion and peace movements was assessed as an important element in influencing Western European governments on the need to support the Intermediate Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty negotiations between the United States and the Soviet Union. The inner workings of the Reagan administration in the context of the overall nuclear and space talks were also discussed. The picture that emerged was one of a more confused and nuanced posture than is generally considered. For this reason, the panel concluded that although a clear-cut link between arms control negotiations and the end of the Cold War later emerged, this was far from evident when the negotiations were on going.

The conference’s closing roundtable discussed the transformation of the international system following the end of the Cold War. The panelists underlined that it is impossible to pinpoint a single element that led to the end of the Cold War, just like no single cause can be used to explain its origins. Therefore, both the beginning and the end of the Cold War need to be studied and explained taking into account multiple factors and actors. The panel then focused on the key developments that followed the Cold War’s ending: the transformation of American power and the consequent US hegemonic position in world affairs. A related factor was the spread of capitalism that, without the socialist challenge, became more exclusive. The panelists also discussed how the immediate post-Cold War was characterized by a moment of positive internationalist hopes on the universalistic spread of democracy and liberal values. This was, however, followed by disillusion, as war seemed to be re-legitimized on the basis of humanitarian interventionism. The panel concluded that although the Cold War and its ending certainly mattered in shaping the international system that emerged in the 1990s, it mattered in ways that we may not yet be able to fully understand.

Written by Barbara Zanchetta and Riina Turtio

The conference resulted in following publication.

New Perspectives on the End of the Cold War. Unexpected Transformations?

New Perspectives on the End of the Cold War. Unexpected Transformations?

Edited by Bernhard Blumenau, Jussi M. Hanhimäki, Barbara Zanchetta

London: Routledge, 2018