Gabriel Geisler Mesevage

PhD Candidate/Department of International History, IHEID, Geneva

Papiers d'actualité/ Current Affairs in Perspective

Fondation Pierre du Bois

No 7, novembre 2013

Read, save or print the pdf version of this article.

At midnight on September 30th 2013, the US government went into shutdown due to a failure to agree to a budget. The shutdown lasted until October 17th when a temporary funding bill was passed. The bill pushes back the date for passing a budget until January 15th. This was the 18th time in US history that the government had shutdown, and the January 15th deadline does not bode well for it being the last.

The cause of the recent shutdown was the inability of the lower chamber of Congress (the House), the upper chamber of Congress (the Senate), and the Office of the President to agree to either an interim or a full-year budget. When Congress fails to pass an annual spending bill or a temporary continuing resolution, all federal agencies and programs must cease operations under the Antideficiency Act. The Antideficiency Act is the legislation that implements Article I, Section 9, of the Constitution, which stipulates that “No Money shall be drawn from the Treasury, but in Consequence of Appropriations made by Law.” [i] The only federal employees excepted from the Act are those who respond to “emergencies involving the safety of human life or the protection of property.” [ii] The immediate effect of the failure to pass a budget is that federal employees are sent home without pay. The exact number of federal employees who were furloughed on October 1st is unknown; in the 1996 government shutdown, it was approximately 800,000. [iii]

The effects of government shutdown are significant. Beyond the immediately observable impact of shuttered monuments and closed museums, the shutdown suspends the programs of several core regulatory agencies such as the Food and Drug Administration – which will not be conducting food safety inspections during the shutdown – and has interrupted research activities at the National Institute of Health. The economic impact for the affected Federal workers is severe. For the period in which government is shutdown Federal employees do not draw a paycheck, and although historically furloughed workers have always received back-pay for the period in which they were furloughed, this is not a requirement of the law. [iv]

The proximate cause of the most recent government shutdown was a fight between Republicans and Democrats over the funding and implementation of the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act, better known as Obamacare. The Affordable Care Act is widely viewed as the signature legislative achievement of Obama’s two terms in office. It was signed into law in 2010, and since then underwent judicial review, with most of the law being upheld by the Supreme Court in June 2012. [v] The law is fiercely opposed by the Republican Party, and a faction of the Republican Party usually referred to as the ‘Tea Party’ adopted the legislative strategy of using their control of the House of Representatives to put forward budget proposals that would defund Obamacare. The Senate – which is majority controlled by the Democrats – refused to pass a budget that would have defunded the healthcare law and insisted that Republicans in the House pass a ‘clean’ budget. For as long as the House refused to table a bill that would pass the Senate and avoid a presidential veto, the Government remained shut down.

The Budget Appropriations Process

The process of US budgeting, as described above, is often viewed as bizarre and inexplicable to those accustomed to a parliamentary system. Within a parliamentary structure gridlock between the executive and the legislature so profound so as to paralyze government functioning is essentially impossible: antagonism between the executive and legislature would bring down the government prompting elections. This is because parliamentary systems draw the executive from the governing coalition in the legislature – thus outright antagonism between these two bodies suggests a crisis in confidence of the governing coalition and the need to form a new government.

The US system of checks-and-balances between the institutions of government is often credited to the intentions of the framers of the Constitution. The argument is that the Constitution was written in the shadow of concerns about executive overreach, and that the system of countervailing powers between the respective branches was designed to constrain executive power at the risk of occasional gridlock. There is a kernel of truth in this view, but it overstates considerably the framers’ tolerance for gridlock.

In her 2003 book, Sarah Binder examined the history of government gridlock. She argues forcefully that Hamilton and Madison were opposed to the idea that a minority might use its veto point to impose its agenda. [vi] When the idea was proposed that more than a majority might be necessary for the passage of a bill, Madison mooted the idea arguing that “it would be no longer the majority that would rule; the power would be transferred to the minority.” [vii]

But if gridlock is not the product of constitutional design, where did it originate? A good case can be made that the type of shutdown the US government is currently undergoing owes more to the evolution of US political parties, changes in the interpretation of the legislation governing shutdown, and the increasing ideological polarization of American political life than it does to the intrinsic structure of US institutional design. This can be seen by an examination of past episodes of government shutdown.

Government Shutdowns: A brief history

The first thing to know about government shutdowns is that they are much more serious now than they used to be. Table 1 below shows all 18 recorded instances of a government shutdown and which political party controlled the executive and respective houses of the legislature at the time

|

Starting Date |

Full Day(s) of Gaps |

President |

Senate |

House |

|

30th Sep 1976 |

10 |

Ford |

Dem |

Dem |

|

30th Sep 1977 |

12 |

Carter |

Dem |

Dem |

|

31st Oct 1977 |

8 |

Carter |

Dem |

Dem |

|

30th Nov 1977 |

8 |

Carter |

Dem |

Dem |

|

30th Sep 1978 |

17 |

Carter |

Dem |

Dem |

|

30th Sep 1979 |

11 |

Carter |

Dem |

Dem |

|

20th Nov 1981 |

2 |

Reagan |

Rep |

Dem |

|

30th Sep 1982 |

1 |

Reagan |

Rep |

Dem |

|

17th Dec 1982 |

3 |

Reagan |

Rep |

Dem |

|

10th Nov 1983 |

3 |

Reagan |

Rep |

Dem |

|

30th Sep 1984 |

2 |

Reagan |

Rep |

Dem |

|

3rd Oct 1984 |

1 |

Reagan |

Rep |

Dem |

|

16th Oct 1986 |

1 |

Reagan |

Rep |

Dem |

|

18th Dec 1987 |

1 |

Reagan |

Dem |

Dem |

|

5th Oct 1990 |

3 |

G.H.W. Bush |

Dem |

Dem |

|

13th Nov 1995 |

5 |

Clinton |

Rep |

Rep |

|

15th Dec 1995 |

21 |

Clinton |

Rep |

Rep |

|

30th Sep 2013 |

16 |

Obama |

Dem |

Rep |

Table 1: Federal Government Shutdown [viii]

What is immediately apparent from the table is that in the 1970’s under Ford and Carter shutdowns were more frequent and longer in duration than they have been under Reagan and Bush. In addition, the Democrats controlled both houses during Carter’s presidency – thus the conflict over the budget was in part an intraparty dispute – in this instance a series of disputes over whether federal health benefits and Medicaid could be used to pay for abortions. [ix] However, these earlier shutdowns rarely entailed the scale of disruption that is common today. The Antideficiency Act – which governs the implementation of a government shutdown – was interpreted by government agencies with wide latitude, and few workers were furloughed as a result of the budget dispute.

In 1981, Reagan’s Attorney General Benjamin Civiletti issued an opinion on the legal requirements of the Antideficiency Act, giving it the character it has today. [x] The stricter interpretation raised the costs of government shutdown; consequently, of the 9 government shutdowns that occurred between 1981 and 1990, none of them lasted more than 3 days. Given the significant costs of shutdown, both sides of the dispute were motivated to rapidly find a solution. This pattern finds support in the political science literature, wherein the length of shutdowns in state legislatures seem to vary with the costs associated with failing to come to a deal. [xi]

Although costly government shutdowns might incentivize deal-making, they make the problem much worse when lawmakers cannot resolve their differences. And they make it significantly more likely that shutdowns will arise from deep ideological divisions wherein both parties are loath to compromise. We can see the beginnings of this process at work in the two 1995 Federal Government shutdowns – the longest of which lasted 21 days.

The two shutdowns of 1995 were driven by disputes between the newly elected Republican majorities in the House and Senate and President Bill Clinton over projections for balancing the budget and cuts to entitlement programs. [xii] The newly elected Republican House, led by Speaker Newt Gingrich, held a conception of the role of government far removed from that of the Clinton White House. The stalemate over the shape of the budget dragged out for 21 days – the longest in US history.

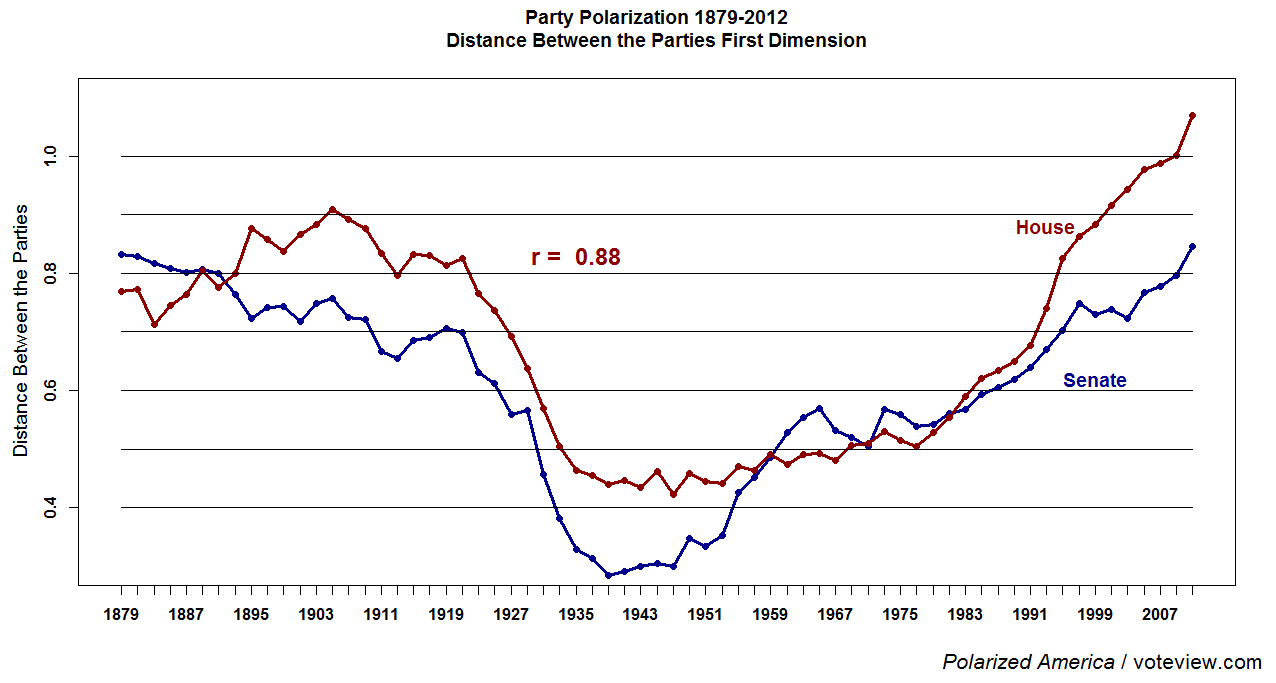

Part of the problem in negotiating a compromise in 1995 was that the ideological positions of the two parties were steadily drifting apart. Measures of ideological polarization used by political scientists – such as the widely used DW-nominate score – indicate that the ideological ‘distance’ between political parties have been steadily increasing since the 1970’s, as can be seen in Figure 1. Political polarization in the current House and Senate are the highest they have been since the reconstruction era (1865 to 1877) in the aftermath of the US Civil War. In another paper, Poole and Rosenthal and their co-authors make the case that most of the divergence comes from the Republican Party moving rightward. [xiii]

(Click image to enlarge)

Figure 1: A measure of the ideological distance between Republicans and Democrats, 1879 to 2012 [xiv]

Political polarization between the parties is abetted by changes in campaign financing laws and the redrawing of district boundaries that make districts more ideologically homogeneous. These two processes isolate individual representatives from majoritarian opinion. For instance, in the most recent government shutdown several polls indicated that the public blamed the Republican Party, and the approval rating of the party overall fell to 24%. [xv] Despite this drop in popularity certain Republicans in the House and Senate still argue that the shutdown was worthwhile and that the ultimate budget deal was a mistake. This can be accounted for by examining how their campaigns are financed and who elects them.

Campaign finance laws increasingly allow small groups – or even individuals – to exercise a disproportionate say in the electoral process. In the 2012 election 0.01% of the population accounted for roughly 40% of all campaign contributions. [xvi] In addition, congressional districts were redrawn (as a result of the 2010 US census) prior to the 2012 elections. The redrawing of congressional districts is usually done in such a way as to make them more secure for the political party that controls the legislature and governorship of the state that is redistricting –a process known as ‘gerrymandering’. Gerrymandering results in a representative’s district being more extreme in their ideological composition than the general population. This makes it harder for candidates to compromise without jeopardizing their chance of winning their party’s primary race. With ideologically homogenous electoral districts, and with special interests able to finance primary challenges out of pocket, it can be very personally costly for a Senator or Representative to compromise.

That the more ideologically extreme House Republicans are afraid to compromise because of fear of a primary challenge is easily observed. When Senate Republicans entered into negotiations with the Democrats, the reactions of House members were apoplectic. The New York Times captured the response well in a quote from Republican Representative Tim Huelskamp of Kansas “We’ve got a name for it in the House: it’s called the Senate surrender caucus… Anybody who would vote for that in the House as a Republican would virtually guarantee a primary challenger.” [xvii]

The foregoing analysis demands a pessimistic conclusion. Congressional control of the ‘power of the purse’ was an institutional design of the US Government intended to restrain executive overreach. But the interpretation of how that power would be implemented in the case of a failure to pass a budget – the interpretation of the Antideficiency Act – has made the effects of this power more severe than anticipated. Coopted by the parties, as well as by intra-party factions in the 1970s, control of the budget process became a tool for extracting compromises in negotiations over political objectives.

But as the parties, and the Republican Party in particular, have drifted from the ideological center, compromise has become increasingly unattainable, resulting in the 21-day 1995 shutdown and the 16-day shutdown this year. Since then, too, changes in the composition of electoral districts and the financing of campaigns have made electoral results increasingly unresponsive to public opinion. These processes are ongoing and suggest that far from reform, we should anticipate growing government dysfunction in years to come.

The January 15th 2014 deadline for agreeing to a new budget is unlikely to escape these dynamics. The Tea Party faction within the Republican Party – the faction that adamantly opposed compromise in the last government shutdown – is already interpreting the last budget crisis as the start of more sustained opposition. In contrast, their more centrist colleagues resent the impact on the party’s image. [xviii] The Tea Party is unlikely to be happy with an easy budget approval process in January. What remains to be seen is whether their fellow Republicans will risk the unpopularity of another government shutdown, or would prefer to risk an open conflict within their own party.

[i] Cited in Clinton T. Brass, “Shutdown of the Federal Government: Causes, Processes, and Effects,” Congressional Research Service, RL34680, 25 September 2013, pp. 3.

[ii] The Antideficiency Act (31 U.S.C. §1342).

[iii] Ibid. pp. 9.

[iv] Ibid. pp. 9.

[v] National Federation of Independent Business et. al. v. Sebelius, Secretary of Health and Human Services, et. al. 567 US (2012).

[vi] Sarah Binder, Stalemate: Causes and Consequences of Legislative Gridlock, Washington: Brookings Institute Press, 2003, pp. 9.

[vii] Madison in Federalist Papers, 58, quoted in Ibid. pp. 9.

[viii] The data for this table was taken from Jessica Tollestrup, “Federal Funding Gaps: A Brief Overview,” Congressional Research Service, RS20348, 23 September 2013, pp. 3.

[ix] Dylan Mathews, “Here is every previous government shutdown, why they happened and how they ended,” Washington Post, September 25th 2013, available at http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/wonkblog/wp/2013/09/25/here-is-every-previous-government-shutdown-why-they-happened-and-how-they-ended/ [accessed 13 October 2013].

[x] Jessica Tollestrup, “Federal Funding Gaps: A Brief Overview” Congressional Research Service, RS20348, 23 September 2013, pp. 1.

[xi] Carl E. Klarner, Justin H. Phillips, and Matt Muckler, “Overcoming Fiscal Gridlock: Institutions and Budget Bargaining,” The Journal of Politics, Vol. 74, No. 4, 2012, pp. 992-1009.

[xii] Dylan Mathews, “Here is every previous government shutdown, why they happened and how they ended,” Washington Post, September 25th 2013, available at http://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/wonkblog/wp/2013/09/25/here-is-every-previous-government-shutdown-why-they-happened-and-how-they-ended/ [accessed 13 October 2013].

[xiii] Adam Bonica, Nolan McCarty, Keith T. Poole and Howard Rosenthal, “Why Hasn’t Democracy Slowed Rising Inequality?” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 27, No. 3, 2013, pp. 106, Figure 1.

[xiv] The graph is from the joint website of political scientists Howard Rosenthal and Keith Poole, available at http://voteview.com/political_polarization.asp [accessed 15 October 2013¨.

[xv] See for instance Josh Barro, “New Poll Shows Shutdown Has Been a Catastrophe For Republicans,” Business Insider, available at http://www.businessinsider.com/poll-government-shutdown-gop-debt-ceiling-popularity-favorability-approval-2013-10 [accessed 15 October 2013].

[xvi] Adam Bonica, Nolan McCarty, Keith T. Poole and Howard Rosenthal, “Why Hasn’t Democracy Slowed Rising Inequality?” Journal of Economic Perspectives, Vol. 27, No. 3, 2013, pp. 111.

[xvii] Quoted in Michael D. Shear and Jeremy W. Peters, “Senators Near Fiscal Deal, but the House Is Uncertain,” New York Times, October 14th 2013, available at http://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/15/us/politics/seeking-deal-to-avert-default-lawmakers-to-meet-obama.html?hp&_r=0 [accessed October 14th 2013].

[xviii] Manny Fernandez, “Texans Stick with Cruz Despite Defeat in Washington,” New York Times, October 18, 2013, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/10/19/us/politics/texans-stick-with-cruz-despite-defeat-in-washington.html?ref=tedcruz [Accessed 04 November 2013].

Last Updated on Tuesday, 19 November 2013 20:10